declarative model是最简单, 最实用的模型. 也是大部份现代语言的基础. declarative风格关注于what, 而不是how. 你需要表明你要什么, 而不是指定怎么做

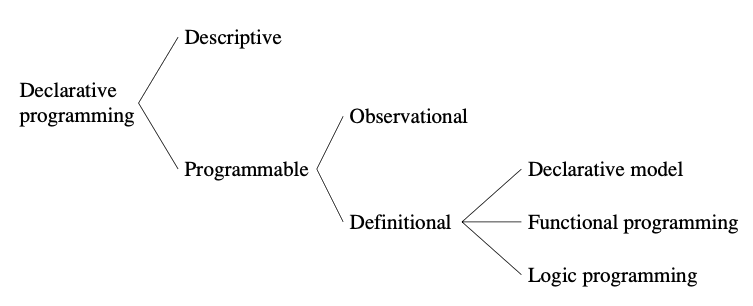

声明式模型的分类, from[1]

declarative语言分为几种.

- 最简单的declarative语言是纯描述性的, 譬如html.

- 与此对应的是可编程语言. 可编程的声明式语言又分为两个l类.

- 一类是可被观察的语言, 这里可被观察特指interface的定义和暴露, 例如protobuf.

- 另一种是可定义的语言, 即编写可运行程序的语言, 它又包含三种风格, 分别是

declarative model, functional programming model和logic programming model, 这里介绍第一个, 后两个稍后会介绍.

模型的必要组成部份¶

declarative模型指出了程序必要的几种元素. 在Core的基础上它额外加入了变量, 函数和分支判定这三个概念.

变量¶

变量引入了 variable binding 和 Destructuring这两个概念.

变量绑定¶

变量绑定即把右侧的值绑定到左侧的对象, 也被称为赋值. 在declarative model中变量一旦绑定, 其值是不可修改的. 换句话说, 这个模型中只有immutable变量.

Destructuring¶

如果我们把赋值做成通用的样子, 改变=操作符的定义, 从简单的赋值发展为"进行若干次赋值, 最终使左右两边的表达式相等", 这就是赋值的通用版 -- destructuring. 譬如

1 = 1, 左右两边都是常量, 虽然没有意义, 但仍旧是正确的语句a, 1 = 2, 1, 也是正确的语句, 最终a=2head | tail = [1 2 3], 最终head=1, tail=[2, 3]tree(val, left, null) = tree(1, null, null), 最终val=1, left=null

变量声明的风格¶

变量的声明也有不同风格, 在一些语言中, 声明变量是个单独的语句. 在另一些语言中, 声明变量的同时也创造一个代码块, 变量只在这个代码块中有效, 我们也称之为本地变量local variable. 之所以这样, 是为了限制变量的可见性, 在代码块之外, 变量是不存在的.

1 2int num = 1; printf("%d", num);

1 2(let ((num1 1) (num2 2)) ; 在let表达式中定义num1和num2 (format t "~A ~A" num1 num2))

函数的定义和调用¶

除了少数声明式语言之外, 函数的声明和调用几乎做到了全网统一, 只有细微的风格差别.

- 声明时指定: 函数名(可选), 参数列表, 返回值类型(可选), 函数体

- 调用时指定: 函数名或函数本体, 参数列表

1 2 3void add(int a, int b) { return a + b; }

1 2 3function add(a, b) return a + b end

1 2def add(a, b): return a + b

1 2 3func add(a int, b int) int { return a + b }

1 2(defun add (a b) (+ a b) )

1 2 3fun {add a b} a + b end

1 2add :: (Num a) => a -> a -> a add a b = a + b

add(1, 2) // in most of the languages

add 1 2 // in haskell

(add 1 2) // in lisp

{add 1 2} // in oz另外, 函数可以随处定义, 甚至嵌套定义.

1 2 3 4 5 6def outer_func(): # define inner_func inside of outer_func def inner_func(): print("do something") return inner_func

分支判定¶

第三个概念是分支判定. 通常形态为if/else, switch/case, match/case

if/else是最通用且最简单的分支语句, 只需要一个bool值或对应表达式就能选择不同分支进行执行.

1 2 3 4 5x = 1 if x > 1: print("x gt 1") else: print("x le 1")

- 另一种则是

switch/case语句. 普通的switch给定一个值, 判断是否命中某个具体值的分支.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11switch (x) { case 1: // do something break; case 2: case 3: // do something else break; default: // default case }

- 更高级的switch, 譬如一些语言中的

match / case等关键词, 则给定一个数据对象, 判断其是否命中一种模式, 并解包数据.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29let x = 4 match x { 1 => { /* do something */ } 2 | 3 => { /* do something else */ } _ => { /* default case */ } } enum Message { Quit, Move { x: i32, y: i32 }, Write(String), ChangeColor(i32, i32, i32), } let msg = Message::Move { x: 1, y: 2 }; match msg { Message::Quit => { println!("Quit message received"); } // destructuring msg Message::Move { x, y } if x == y => { println!("Moving diagonally to ({}, {})", x, y); } Message::Move { x, y } => { println!("Moving to x: {}, y: {}", x, y); } }

以上就是declarative model引入的新特性.

如何写声明式代码¶

这么瘦的语言模型怎么写程序? 让我们来看几个例子.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11def sqrt(x): def improve(guess: float) -> float: return (guess + x / guess) / 2.0 def good_enough(guess: float) -> bool: return abs(guess * guess - x) / x < 0.00001 def sqrt_iter(guess): return guess if good_enough(guess) else sqrt_iter(improve(guess)) return sqrt_iter(1.0)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29def merge_sort(lst: list) -> list: def split(lst: list) -> tuple[list, list]: return lst[:(len(lst)//2)], lst[len(lst)//2:] def merge(lst1: list, lst2: list) -> list: match (lst1, lst2): case ([], l): return l case (l, []): return l case ([h1, *t1], [h2, *t2]) if h1 < h2: return [h1, *merge(t1, lst2)] case ([h1, *t1], [h2, *t2]) if h1 >= h2: return [h2, *merge(lst1, t2)] case _: return [] match lst: case []: return [] case [x]: return lst case _: part1, part2 = split(lst) return merge(merge_sort(part1), merge_sort(part2))

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15def new_stack(): return [] def push(stack, elem): return [elem] + stack def pop(stack): match stack: case [head, *tail]: return head, tail case _: return None, stack def is_empty(stack): return len(stack) == 0

从上面的例子我们可以看到, 虽然时间复杂度并不高明, 但declarative model的确可以实现算法和数据结构. 程序表现为一系列函数的组合, 函数互相调用, 甚至递归调用. 并且很多时候我们都在使用高阶函数[2]简化代码结构.

如何写好声明式代码¶

算法idea需要多多积累. 此处无捷径. 递归的写法也需要多多练习. 在熟悉各种递归的写法之后, 关于状态的感知能力也会得到锻炼.

关于递归的步骤和写法, 有很多参考材料, 这里给出两个:

[1]中给出递归的基本步骤是:

Paul Graham在[3]中提到了另一种写递归的视角

计算机科学家, 作家, 企业家和投资人

著名的创业加速器,其中国分部是奇绩创坛的前身

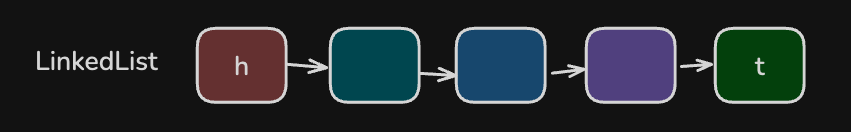

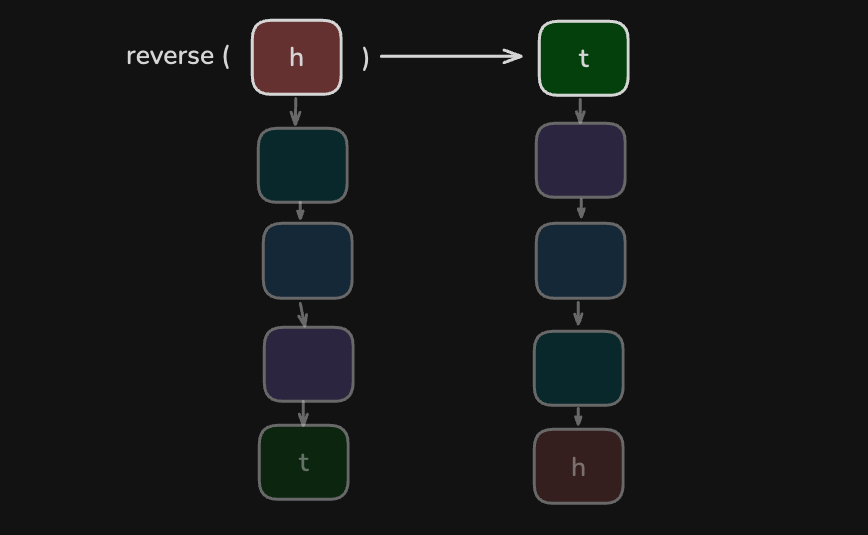

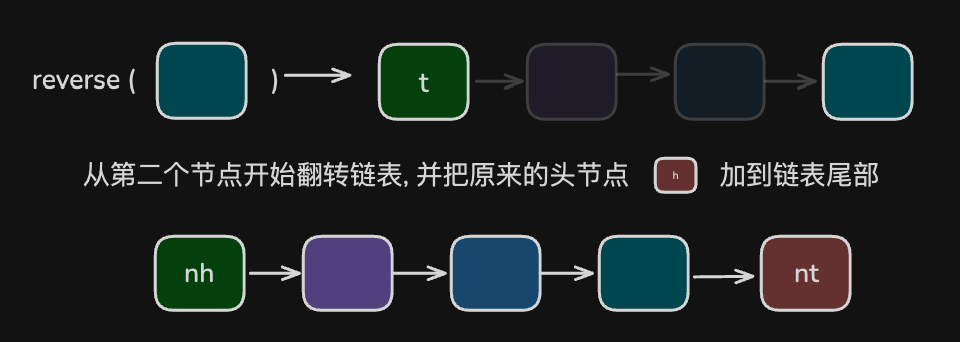

以翻转链表为例子. 首先我们定义链表节点.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7from dataclasses import dataclass from typing import Any, Optional @dataclass class Node: val: Any next: Optional["Node"]

紧接着, 我们有如下步骤

1 2 3# 定义函数: 传入链表头节点, 返回翻转后链表的头节点 def reverse(head: Node) -> Node: ...

定义函数(参数列表, 返回值)以确定函数的运作方式

1 2 3 4 5 6 7# 调用本函数, 实现函数体, 并得到最终结果 def reverse(head: Node) -> Node: sec = head.next new_head = reverse(sec) # 递归调用 sec.next = head head.next = None return new_head

调用自身, 实现函数体

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13# 检查递归停止条件 def reverse(head: Node) -> Node: if not head: # add defence raise TypeError("head must be a Node") if not head.next: # stop condition return head sec = head.next new_head = reverse(sec) sec.next = head head.next = None return new_head

在写递归的时候也要注意数据结构是否是递归定义的. 如果是, 那么最好弄清楚这个定义. 因为知道数据类型是如何递归定义的能够很好的指导递归函数的编写.

很巧的是, 非常多的数据类型都可以被递归定义.

譬如如果我提前弄清楚了链表类型的递归定义是:

data LinkList = Nil | Node(val, LinkList)那么我就知道递归函数中至少有两个分支, 一个处理Nil, 另一个处理Node, 并且处理Node时需要递归.

循环的缺席¶

循环作为语法的基础元素之一, 存在于大部分语言中, 但是declarative model并不提供for / while这样的关键词, 它用递归函数来满足循环的需求.

我们可以定义iterate函数来达到类似循环的效果. 这里state是状态, 是可以自己定义的某种数据, is_done和transform都是函数, 其参数都是状态state. is_done返回boolean, transform返回一个新的状态.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13from typing import Any, Callable def iterate(state: Any, is_done:Callable[[Any], bool], transform: Callable[[Any], Any]): """ is_done(state) -> bool transform(old_state) -> new_state """ if is_done(state): return state return iterate(transform(state), is_done, transform)

有了iterate函数之后, 实现sqrt会变得很简洁.

1 2 3 4 5 6def sqrt(x): return iterate( 1.0, lambda g: abs(g * g - x) / x < 0.00001, lambda g: (g + x / g) / 2.0 )

当然这样的iterate函数, 并不如for / while组合出来的循环灵活好用, 但它会让你感知到循环和状态之间的关系, 也会让你觉察到原来命令式编程中隐藏了这么多复杂的状态和状态的改变.

虽然iterate函数本质上是递归调用, 但性能上并不拉跨, 因为它实现了一种特定的递归形式--“尾递归”, 而尾递归在很多语言中都有相应的性能优化.

另外从上面的例子也可以看到, declarative model在整个函数体中, 不会去修改状态, 而是创建一个新的状态, 进行下一次递归. 换句话说, 状态是可以改变的, 只不过状态的改变总是出现在参数列表中, 而不是函数体中, 状态是隐式改变的.

和函数式编程的关系¶

既然declarative model没有所谓变量, 它和函数式编程有什么关系呢?

在很多人看来declarative model就是就是函数式模型, 只不过相比于“纯函数式”模型, 在处理副作用和IO等方面, 代码有很大区别.

什么时候使用声明式模型¶

那么在实战中如何运用declarative model呢?

虽然declarative model可以用来实现各种系统, 但就实际情况来说, 我基本上是在实现一些抽象算法, 业务无关的通用util的时候使用.

语言的表现力是一把双刃剑. 表现力越强, 写一些复杂算法就越简洁, 但理解难度也越高. 反之, 表现力弱, 写复杂算法就越冗长, 但理解起来也相对容易. 这是一个客观现象.

Declarative model的表现力很弱, 应对复杂多变的业务时, 这个模型力有不足, 编写复杂的业务算法时, 写出来的代码也比较长.

但是对于开发一些业务无关的通用算法, 使用declarative model很合适, 因为问题规模不大, 代码比较容易实现, 写出来也不会太冗长. 而且声明式代码易读, 易理解的优势能充分发挥.

到底用不用declarative model, 实战中, 有三条标准, 分别是: 正确性, 执行效率和可读性.

- 正确性是前提, 如果declarative model中缺少一些功能(譬如try / catch)导致代码不对, 这种情况就要采纳比declarative model强大的模型.

- 如果算法要求有极好的性能, 并且要极致优化, 那也不适用. 因为声明式风格一定会损失效率, 因此它的代码效率不会很极致. 不过所幸, 要求算法有极好性能的系统其实非常少, 就算在这种系统中, 需要极致优化的代码也只是一小部份而已.

- 可读性是第三个重要标准. 代码可读性同时受制于代码长度和代码难度. 可以说

代码可读性=代码长度x代码难度. 如果使用declarative model能够极大降低代码难度, 同时又不会显著增加代码长度, 那就应该使用它.

总之, 实战中, 我们不会为了写声明式代码而写, 而是写完代码之后才发现自己使用了declarative的写法.

你也可能会问, 我用的语言是否支持declarative model呢?

强力的语言, 其中基本都会有一个declarative model的子集. 只要你能用declarative model有限的特性把算法写出来, 写的简单易懂, 并且性能上过得去, 你就已经使用了declarative model.

不去使用过于复杂的特性, 而是使用刚好足够的特性, 把代码实现的恰当好处, 这也是精益编程的重要实践.

为什么要掌握这个模型?¶

这个模型值得花时间学习和使用吗?

值得, 因为它能够写出优雅, 好理解, 好维护, bug少的代码.

同时它也是一种大脑体操, 帮助你理解类型的定义, 递归的设计, 程序状态的抽象.

如果你写算法, 理解算法有困难, 那十分推荐你掌握并实践declarative model.

另外这种简单的模型, 也是几种不同语言模型分支的交汇处. 要理解其他语言, 理解declarative model就是必经之路.

原文为

- You have to show how to solve the problem in the general case by breaking it down into a finite number of similar, but smaller, problems

- You have to show how to solve the smallest version of the problem—the base case—by some finite number of operations.